|

||

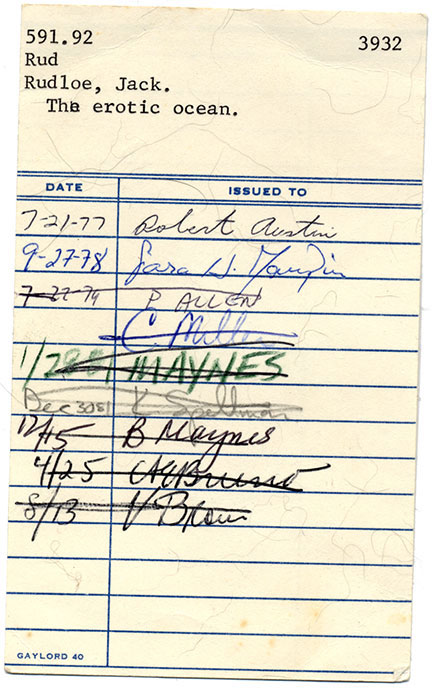

The Erotic Ocean, library unknown (book discarded) Hard not to fascinate on the "Gaylord 40" on the lower left. The card was made by Gaylord Brothers, a company founded in 1896 in Syracuse, NY. According to Dana Ferrel at Gaylord, the cards are still in production (the one above is 05—buff, a color I only attribute to cats, one of only five colors still available (02—blue, 05—buff, 10—green, 19—salmon, 24—white: the gaps in numbering perhaps suggest unsuccessful colors, or colors planned but never executed, to fill the space between salmon and white, resigned now to history)) some forty years later. I am accustomed to everything I love slowly disappearing. I'm surprised to find this market still exists. They're such simple things, clear in their utility, stiff enough to last a century with gentle use. Not meant to persist for long. We don't think of the checkout records as part of what the library offers, and it no longer does, not most of them, not publicly. The records are there, as any librarian knows, digitally now, encoded in databases, and the government may come calling for the records of those who checked out Mein Kampf or The Anarchist's Cookbook, as they did just after the attacks of September 11th and the Homeland Security Act. Now, a dozen years later, we are accustomed to the collection of our data. We have been willing, mostly, to trade it away for convenience, for services that seem otherwise free. This is what we have to offer, the aggregated data of our behavior, our shopping and our surfing preferences, our movements throughout our days, what we read or thought we might want to read, or what we at least checked out ambitiously. To know that our histories are worth something, that they're kept, that they trail us like a wide lace net unfurling over choppy lake water, as fine and long as the neural pathways in our brains, of which our memories are made, is to know it's all available if we are not careful, that we are available, that we offer something, which is on some days more than it seems. |

||